FAULTY ‘CHECK VALVE’ APPEARS TO BE CAUSE OF GRAVENHURST WATER SHUT DOWN FROM NOV. 27-30

Mark Clairmont | MuskokaTODAY.com

GRAVENHURST — A little $5 check valve looks to be the cause of a recent water shut down here.

And not a mislabelled fluoride drum that helped lead to a four-day water scare due to “low” levels of the chemical routinely added to prevent tooth decay.

That was the early, preliminary finding in the hours after a 2:05 a.m. alarm Saturday Nov. 27, which caused a run on bottled water, threw the town in to a tizzy — and had dozens of district, third party, health unit and lab staff scrambling with how to deal with the alarming problem as residents slept safely in bed unaware that when most awoke they’d have no running water.

And no idea of what was wrong, how to deal with it or when they’d have water to take their pills, make morning coffee or have a shower.

But within 12 hours they had found the problem.

It seems the ball on the drum valve was stuck open, allowing water to trickle back into the drum, which feeds fluoride into the town’s district-operated water system.

That resulted in the low fluoride reading that set off alarm bells literally and figuratively.

Final results of a fuller investigation and review, including the public fallout, aren’t expected for “five or six months,” said Fred Jahn, commissioner of engineering and public works at the District of Muskoka.

After a quick assessment of the initial situation, Jahn said he “didn’t hesitate” to shut down the plant on the Beach Road, which the district only upgraded last year and that gets its water from a large pipe coming in from nearby Lake Muskoka.

MuskokaTODAY.com spoke to Jahn about why it happened.

While he has already briefed council in a zoom meeting in the week after, he says he will be presenting the findings of the “water emergency” at the EPW committee meeting on Jan. 19.

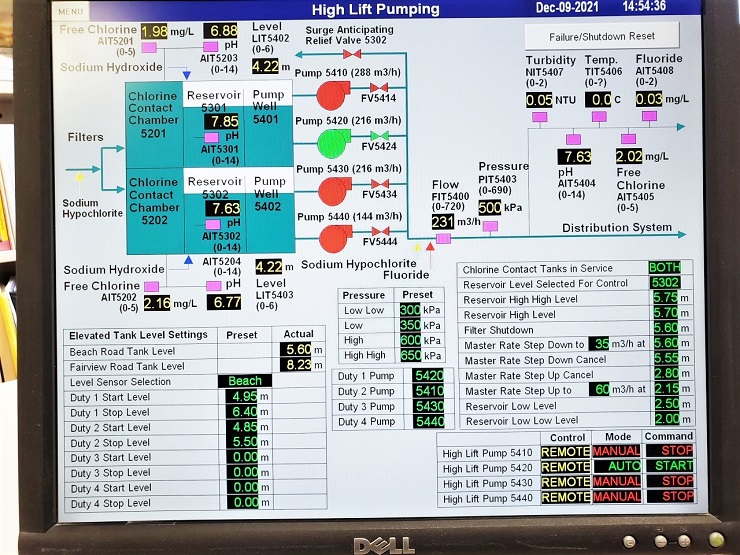

But in an recent interview with MuskokaTODAY.com a week after, he said the water is “constantly monitored and tested 24/7” at its nine drinking water and waste water plants, which he said are staffed during weekdays and by employee operators on-call at night, on weekends and during off-hours.

“It’s very sophisticated,” said Jahn. “If anything isn’t working the way it should then an alarm goes off — and during the day an operator will tend to it. If it’s outside hours we have an on-call operator to answer those situations.”

In addition regular samples are taken from ground pipes to “make sure the proper levels are being maintained,” because there are miles of them that run from the water treatment plant to homes and businesses.

Jahn said Ontario’s Safe Drinking Water Act (2002) regulations are very specific and “we have to demonstrate that we’re meeting them at all times.”

Fluoride isn’t the only chemical that goes into Muskoka’s water. It depends on the water source and its chemistry, he said. (Huntsville and Port Sydney do not have fluoride added to their district water.) There’s also the chloride and soda ash, which act as cleaning agents.

“This simple little $5 check valve that put water back in the drum was the cause of this whole situation. In the middle of the night that wasn’t apparent,” said Jahn, who previously ran the public water system at Rama for 12 years and worked in Muskoka’s private sector at Alcan and Panolam.

He said it was the “first time” he and the district have shut down a plant since he joined the district in 2014 as commissioner of public woks and engineering.

However, last January there was also a major pipe break in Bracebridge that took almost a week to fix; and another smaller one there this past weekend on the same pipeline running from base of the Bracebridge Falls.

“It’s not uncommon for alarms to go off,” Jahn said.

Typically it’s “routine” and “usually there’s an explanation. This time there wasn’t.”

The fluoride was “lower than required to be.”

So the first operator on call responded “immediately.”

“Everything seemed to be working as it should be. The fluoride drum was pumping into the water system.”

But the computer was not getting a fluoride reading, “which was very puzzling.”

Because the same drum was working the day before, Jahn said.

“There was fluoride in the drum and putting it into the water properly.”

A fluoride analyser controls the level and injections into the pump through automated metering.

So what happened?

When the operator on call responded to the alarm but couldn’t determine the cause, he called the plant’s chief operator who was “equally puzzled.”

They think maybe there’s something else in the drum other than fluoride.

“It seemed like a long shot,” added Jahn.

The first two operators then called in the overall responsible operator — who called Jahn at 4:45 a.m.

“I made the decision right on the phone.

“I determined very quickly that we needed to shut down the drinking water system.

“Because when I hear there is a question from my operational licensed staff — that all three have this potential doubt in their minds that there could be something else in the system other than fluoride — I just felt that that was the only decision that could be made.”

And “even though it seemed highly unlikely there could be anything else in it,” Jahn’s first instinct was: “So if there is any doubt about the safety of the drinking water I have to shut it down.

“I mean I just couldn’t take that chance,” even though operators had “never had this issue before.”

The first thing Jahn did was convene the district’s emergency control group, which included all the committee commissioners, the CAO and top staff officials.

“We were on a call by 6 a.m.” with the Ministry of Conservation and Parks (MECP) and the Ministry of Health, which had already been alerted during the night as per standard procedure.

“We needed direction from those two agencies,” said Jahn.

“My first reaction was to have the contents of that drum tested at an external lab to verify what was in the drum.

“What was in the back of our minds is that there could have been more than one liquid. You could have heavy liquid at the bottom and light at the top.

“It seemed really highly unlikely, (but) we rely on those possibilities.”

So Saturday morning one of the operators drove a sample to the lab in Peterborough where they get their testing done.

“The test came in at two o’clock Saturday.

“We found that, ‘yes,’ there was fluoride in the drum — but also water in the drum.

“So that theory we had that there was potentially two liquids in it was right — fluoride on the bottom and water on top.

“And by the time we had that lab result back at 2, we had found the problem. A very simple failure of a component called a ‘check valve,’” said Jahn.

“That caused water from the distribution system to work its way all the way back into drum.”

That’s why they were getting the alarming “low” reading.

“It certainly put our minds at ease that there was fluoride and water and nothing else.

“That was always our No. 1 safety question: ‘What was in the drum?”

Jahn did say: “It crossed our minds that there may be something else like a contaminant in it,” which could work its way into the town’s drinking water.

“But the probability of that would be extremely low,” he said.

“But because we couldn’t rule that out in the middle of the night, we had to put public safety and health at the top of our list.

“I didn’t hesitate. It was a decision that had to be made.”

Turning on the water and flushing pipes

But then “putting the fluoride back in (the water system) was not a priority at all.

“The priority was getting the water back on to residents of Gravenhurst.

“All this time we were communicating with the MECP and the medical officer of health (Dr. Charles Gardner). We were meeting in the early hours with officials as well as the mayor (Paul Kelly) and their staff to make sure everybody was on the same page.”

After discovering the cause, Jahn said: “The first thing we did was focus on getting the word out by public communication.

“That was absolutely the No. 1 priority. To let people know why your tap is off — and to await further announcements.”

That was at 7 a.m. when the first emails went out to media.

Then it was “shortly after noon that I had direction from the medical officer of health to turn the water system back on.

“And that was done with a ‘Do Not Use order.’

“We needed to get the water back on, so we could start to flush the system.

“People needed to flush their toilets. They can not drink that water. They can’t wash their hands with it.”

Jahn continued: “Once we had the information that we knew exactly what was in the drum — that was a huge sigh of relief.

“And so based on that information the health unit lifted the ‘Do Not Use’ order and issued the ‘Boil Water Advisory,’” about 4 p.m. Saturday.

“Let me just explain, when you turn the water pressure off there’s the potential that bacteria could find its way into the pipes under ground. And because of that there’s a very specific procedure that you have to do. You have to flush the entire system — like all the fire hydrants.”

That’s what several district staff did throughout town Saturday night with water gushing out onto then cold, snowy streets.

“Once that flushing was complete and the water pressure restored you take a second set of samples and test them. We drove them (again to Peterborough) because this was a time thing — an emergency.”

Because the water act requires separate samples 24 hours apart, on Sunday night another sample was taken for testing, which takes a further 24 hours for the lab to turn around results.

“All those samples have to show zero chloroform and zero fecal lines. We had all those test results back by Tuesday morning showing zero-zero.

“So Dr. Gardner lifted the ‘Boil Water Advisory.’”

The district needed the “OK” from both the health unit and MECP to turn on the water.

“It’s having those extra safeguards in the system to make sure the water is safe,” said Jahn.

Drum had fluoride, but labelling unreliable

As for the drum, he said while there was a problem with the labelling, it still did contain fluoride — but the labelling “did not meet” the district or province’s “very specific” labelling standards.

“That added another level of uncertainty. There was a label on it but it wasn’t the correct one.”

Yet it was still put in to use?

“And again that was part of the question and will be part of the investigation” going forward with an independent incident investigator and consultant, said Jahn.

“As to why this chemical manufacturer sent this drum with labelling the way it was.”

Essentially staff hooked up a drum with the wrong labelling — but it was still the right product, but it ended up being diluted with back-flow water.

Jahn said district procedures do include WHMIS (workplace hazardous material information system) requirements: transportation and handling of chemicals, shipping and receiving, when they are put in service and taken out and shipped back to the supplier.

Those, too, will be part of the investigation, Jahn said, to “focus on just making sure all those actions are understood.”

The investigation will likely last over the winter and in to the spring, he said.

They’ll be “investigating every aspect.

“There’s a lot more than just the label.”

What’s the fluoride supplier got to say?

“They were certainly concerned and should be,” replied Jahn, adding he thinks the name of the company, ironically, was “Reliable.”

“I’m sure that would be high on their priority list from a quality control standpoint to make sure that doesn’t happen again.”

What financial cost to the district?

Jahn’s first “hunch” is that it will be mostly labour costs.

“But not a big cost.”

He said it was more about the “significant” number of staff involved.

“That’s where the cost is.”

He said that on the Sunday there were 40 to 50 district staff going door-to-door to Gravenhurst homes and businesses with hastily written envelopes and letters about the boil water order explaining what happened and how to get free cases of bottled drinking water at the south end of town. A water truck also provided water and pails till Tuesday.

“One of the first things we did was make sure water was available — and people really appreciated that.”

The Salvation Army, Costco and Wahta Springs and some businesses with private label bottle also offered the district water for district distribution and public consumption.

On that Sunday about 1,000 cases alone were handed out by district staff who loaded up trunks as COVID-wary and weary drivers pulled up to piles of loaded pallets.

“It’s very inconvenient when your taps don’t flow,” said Jahn, adding “it’s always a good opportunity to remind residents to make sure they have 48 hours of emergency supplies on hand.

“And to have people sign up for the district’s emergency alert system — because, trust me, it’s the hardest thing to do to get the word out to the general public quickly.

“Things can happen and this is a good example of why there are so many safeguards in place. And why you always want to be prepared for emergencies.”

Muskoka water among most costly in Ontario

“We’re certainly up there in cost and operating,” said Jahn.

He says it’s due to Muskoka’s geography, its size and the number of communities the district supplies water to — like tiny plants in MacTier and Baysville that only serve about 300 people each.

And the high standard demanded by seasonal and permanent residents in a district that largely lives on and off its water.

He maintains that larger cities in the GTA and in Ottawa — where he has visited — can rely on density to bring down costs.

The environmental and infrastructure costs of maintaining similar systems are “almost the same” for large and small cities and towns, he says.

The district only upgraded the Gravenhurst drinking water system last year. Huntsville, he said, is also undergoing the same plant improvements now as part of a move away from its downtown to a new location outside its core.

Muskoka is also now moving ahead with plans to upgrade waste water facilities.

Is district water safe to drink?

“Oh yeah,” Jahn says confidently.

“I’ve got the best operational staff in the world, really. There’s something about district employees. They’re just so dedicated to what they do to serve the public.

“I think the whole incident was a good example of that. It’s unfortunate these things happen. But at the same time I just love how they stepped up and put public interest first.”

Were there any operational errors?

“No,” said Jahn.

“But I want an objective investigation. If anyone made a mistake we just have to own up to it and say so — and correct it and move on.”

Jahn said there were “no flags” when operators received the chemicals and “verified” them by inspecting the packaging.

“But that doesn’t mean that our current system is as good as it could be. I don’t know what I don’t know yet.

“That’s why we’re starting that conversation with the ministry and the health unit to look at best practices and make sure that that doesn’t happen again.”

Jahn said: “As far as I know the key information is that the chief operator found the (stuck) valve when one of the lab tests said there was water in the drum.

“And the only way water could get in the drum is what’s called a ball check — and if that’s stuck open. And so that’s the only possible explanation.

“Unless the fluoride company somehow had water in that drum, which doesn’t seem right either.”

What about the community impact?

The business community was particularly hard hit — especially food establishments.

And they’ve voiced their concerns.

Jahn said he “understands” it’s been a “most challenged year” for them and “that’s unfortunate. They’ve had enough challenges with the pandemic and you name it and then the water gets turned off.”

Have other check valves and drums been inspected?

“Yes.” About 20 of them, Jahn believes. The same with the drums.

Bacteria concerns early on in pipes

Jahn said when the water pressure is off water can leak into the ground water and also back into the pipe, causing “possible bacteria” in the system.

The same goes with water heaters that are known to have bacteria, he said, which was why the district advised they be turned off to prevent similar leakage into pipes.

“That seemed very unlikely.”

A good thing as most people didn’t understand that request or act on it.

But just to be safe and according to the drinking act the district flushed the pipes.

“Just because you don’t think there is bacteria in place you always have to think the worst case.”

Jahn said during zoom calls officials “we’re hearing from everybody at the same time,” providing updates, getting direction, asking questions and trying to understand what was going on for just-in-time decision-making so that information could be conveyed to the public as soon as possible.

“It’s important to keep everybody on the same page.”

Jahn said the whole incident did give him a better understanding of the serious water issues resulting from fatalities in Walkerton and those affecting First Nations residents dealing with decades of water crisis’s up north.

EMAIL: news@muskokatoday.com

28 years of ‘Local Online Journalism’

Twitter: @muskokatoday, Facebook: mclairmont1

Leave comments at end of story

SUBSCRIBE for $25 by e-transferring to news@muskokatoday.com

Or go online to https://muskokatoday.com/subscriptions