INCREDIBLE ‘CAMP 20’ STORY TALE OF ENEMY PoW ‘OFFICERS, GENTLEMEN’

Mark Clairmont | MuskokaTODAY.com

GRAVENHURST — War stories are legend in Gravenhurst, where Norwegian pilots potato-bombed German PoWs swimming in Lake Muskoka.

It’s part of an oddity played out in which opposing forces shared the same streets as “officers and gentlemen.”

Caught between were Canadians and the Veterans Guard.

In the front row for this bizarre show were local residents who would surprisingly see hundreds of feared Nazis marching through town one day, then the next watch as the future king of Norway, Harald, and his royal family would fly over to land at the north end of town at a purpose-built wartime airstrip.

The last “great war” for this generation was 76 years ago — only a distant memory now.

A fun history lesson for ardent archivists like Judy Humphries to share in her popular talks at the library, as she did once again this week so extremely well.

But for those who grew up in Gravenhurst, Camp 20 and Little Norway were only a few miles away from one another, but worlds apart.

An enemy lake compound west of Hwy. 11 and a repatriation flight school in the fields to the east — the demilitarized zone between them being the Muskoka Road main street.

It’s in that historical context that Humphries places her latest archival narrative.

Camp 20 — or precisely Camp Calydor — is the sadly less celebrated of the town’s two war encampments. Its Deutschland dichotomy so dependent on the opposing camp in this sensational story.

As in the funny story of the German swimmers in their barbed water compound, who were dive-bombed by playful Norwegian pilots practising payload drops with rotten potatoes.

Or the start of several sensational prison escapes that began with a tunnel only weeks after opening. Only one of which ended up truly successful.

It’s said that one escapee, a former member of the 1936 German Olympic hockey team, even practised regularly with the Montreal Canadiens before being caught.

And of course the one about pianist Charlie Musgrave, who played ‘There Will Always be an England’ and ‘Rule Britannia’ as the Sagamo ship steamed past the camp.

It’s these and other fascinating facts about Camp 20 that captured the imaginations of 135 people who Zoomed in on the regular history talk; only a few of them who lived through it. But most of them had a connection — family or otherwise — and an interest in preserving the past.

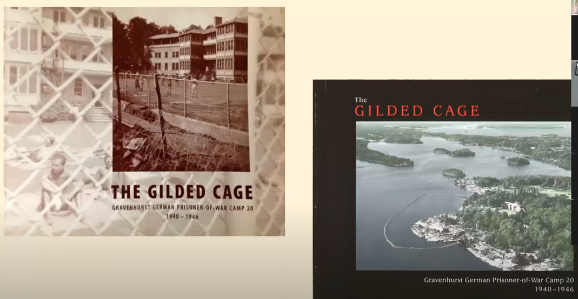

Humphries’ talk was based largely on the definitive, groundbreaking work of the late Cec Porter, a Gravenhurst native and author of two volumes on the camp entitled The Gilded Cage — the title of which says it all.

A year in to the Second World War, Camp Calydor came back to life on June 30, 1940. In just 15 days it was resurrected in the shuttered remains of 34 acres of land bordered to the north by the Calydor and to the south by the Minnewaska tuberculosis sanatoriums.

Its canopy-covered remains camouflaged by decades of new growth to the south of the present day Lorne Street neighbourhood parkette beach.

That’s where few — if any — of today’s teenagers diving off the nearby “Cliffs” along the Ungerman Trail could imagine that PoWs bearly years older than them once swam and splashed in the same summer waters.

The only nod to 20’s hidden history is the rebuilt remains of a fish tank prisoners used to keep their freshly-caught bass and lake trout. That was before they served them up on dinner plates in a camp that by 2021 standards could be easily compared to the Beaver Creek federal minimum security prison across town that came out of Little Norway.

At any time during its five years of existence, Camp 20 “held” close to 500 PoWs “guarded” or barely supervised by some 100 retired Canadians soldiers from the First World War.

The camp was part of Canada’s war effort and eventually came to be designated as a “Black Camp,” as it housed hardened Nazis. Other camps in Canada were considered either grey (German sympathizers and volunteers) or white (conscripted, forced recruits).

It wasn’t unusual for German “officers and gentleman” to sign themselves out on escorted day “paroles” in to town while promising not to escape. Or to work on their large hobby farm out on the leased Passmore family lands where the north industrial park is today.

Many did have to wear big red dots sewn into their blue denim work clothes. They were the onese who didn’t have suitably clean army or air force uniforms to wear out in public.

In winter their hockey team would play local teams while other soldiers studied or read in what was said to be one of the largest libraries north of Toronto.

Almost all took courses provided through the University of Toronto. They even had a symphony, a dance band and a chamber orchestra that entertained in concert each Sunday (A forerunner of Music on the Barge?).

Much of their creature comforts came via the world YMCA and military pay that amassed a small working fortune that allowed them to buy chocolate and even a quart of beer per week. Pictures of the prisoners playing tennis were widely seen

Oddly the PoWs were part of the fabric of a small community at war with Hitler’s “Huns.”

It was not unusual for locals to enter the camp on occasions.

An uncomfortable, if not strangely entertaining — and likely unconscionable — alliance for citizens, as the names on the same main street cenotaphs attest.

Photos weren’t suppose to be taken of the enemy (but they were and still exist in the Gravenhurst Archives and family photo albums), for fear they would get back in to the hands of Germans overseas who could identify them and help escape, which Humphries said was not a “duty” for any soldiers to do.

When PoWs did get re-captured after breaking out in boxes and in bed sheets they were routinely sentenced to only 28 days in the guard house — a Geneva Convention order.

Still the prisoners’ presence and legacy remains to be seen in two sets of granite steps and a long break wall at Gull Lake Rotary Park.

When the camp closed June 29, 1946, Humphries noted it ironically became a resort catering to a wealthy Toronto Jewish clientele.

Since then a few former prisoners have made pilgrimages back to the town and camp site — often as part of family vacations. Many remained in Canada, but none of note in Gravenhurst.

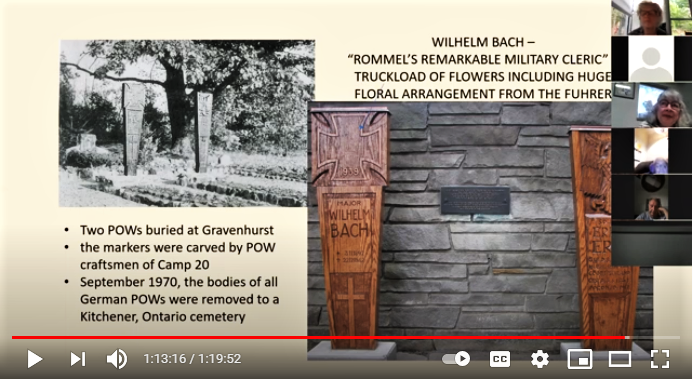

Two were famously buried at the Mickle Cemetery with ornate wooden tombstones, which were eventually in 1970 repatriated to Kitchener (formerly Berlin) along with all 167 German PoWs who died in Canada.

A lot of the camp’s materials and supplies were dispersed about the town after the war, including hockey equipment given to underprivileged kids.

If you venture off the Ungerman Trail today you’d be hard-pressed to see any remote remnants of the camp, save for the odd footing of a barbed wire fence if you look hard. The town ploughed it all under, the land was sold and houses now sit where Luftwaffe colonels once raised their right hand in salute to their fuhrer after first raising both hands in surrender.

To view Humphries’ YouTube presentation click here or go to the library website here.

See more on the war in the Gravenhurst Library’s local history section for Porter’s books

and fellow local author Andrea Baston’s book Exile Air on Little Norway.

Email news@muskokatoday.com

Celebrating 27 YEARS of ‘Local Online Journalism’

Follow us on at Twitter @muskokatoday & on Facebook at mclairmont1

Leave your comments at end of story.

Send Letters to the Editor at news@muskokatoday.com

SUBSCRIBE for $25 by e-transferring to news@muskokatoday.com

Or go online to https://muskokatoday.com/subscriptions

September 2, 2021 @ 12:05 pm

Interestingly enough no mention of the Jewish men who were kept on this camp with the Nazis.

I wonder why?